[ad_1]

In 1941, a couple from New York bought an undeveloped parcel of land in Beverly Hills for fourteen thousand dollars from the writer Dorothy Parker, the most fearsome wit at the Algonquin Round Table. James Pendleton, an interior designer and art dealer of Regency and Baroque pieces, and his wife, Mary Frances, who went by Dodo, craved a particular vision of California living. They imagined a landscape of eucalyptus trees and rose gardens, with a pool house suitable for high-life entertaining—a Xanadu escape from their place in Manhattan. The Pendletons enlisted the architect John Elgin Woolf, who designed homes for Cary Grant, Lillian Gish, Barbara Stanwyck, and Errol Flynn, to create a one-level house—Dodo had a bad hip—in a coolly sumptuous style that would come to be known as Hollywood Regency.

In 1967, Pendleton sold the house to Robert Evans, who, as the head of Paramount Pictures, went on to oversee a string of era-defining films: “Rosemary’s Baby,” “Love Story,” “The Godfather,” “Serpico,” “Chinatown.” Evans led a life worthy of a film auteur’s attention—glamorous, accomplished, and more than a little sleazy. When he bought the house, which he called Woodland, he had been married twice; he would marry five more times. He became almost as well known as a host as he had been as a producer, throwing bacchanalian parties and entertaining such stars as Dustin Hoffman, Jack Nicholson, and Roman Polanski. In the nineteen-eighties, an addiction to cocaine and an association with a tawdry murder case helped bring his career, and the parties, to an end.

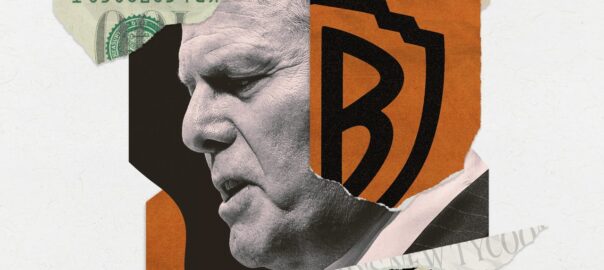

Evans died in 2019, at the age of eighty-nine. Three months later, a media executive named David Zaslav bought Woodland for sixteen million dollars. Though Zaslav was one of a select group of people who could afford this Hollywood palace, he was not part of the town’s aristocracy. Zaslav was then the C.E.O. of Discovery, Inc., the cable corporation whose channels included HGTV, TLC, Animal Planet, Food Network, and the Oprah Winfrey Network. At the time, his greatest claim to fame was the size of his paycheck. In 2014, he was the country’s most highly paid executive, with compensation of a hundred and fifty-six million dollars, mostly in stocks and options. Zaslav, whose teeth gleam a startling white and whose wardrobe skews toward Wall Street leisurewear—logoed golf shirts and zip vests—had a reputation as a shrewd dealmaker, adept at brokering acquisitions. Discovery was something of an entertainment-industry backwater, known for a portfolio of low-cost, lowbrow, highly profitable programs, of the kind you don’t tell co-workers you watch: “Here Comes Honey Boo Boo,” “Wives with Knives,” “Naked and Afraid.” Zaslav, a lifelong New Yorker, had never been involved in managing a Hollywood studio, but he seemed to like the idea of the town. “David has always been on the outside looking in on the content world,” a former Discovery executive told me. “He’s always wanted to be a player in Hollywood.”

In May, 2021, a year and a half after Zaslav purchased Woodland, he was announced as the C.E.O. of a new media company, Warner Bros. Discovery—a vast conglomerate that melded Discovery’s holdings with those of WarnerMedia, which encompassed HBO, Warner Bros.’s film and television studios, CNN, and a suite of cable channels including TNT, TBS, and Turner Classic Movies. Zaslav, the sixty-one-year-old head of a middle-market cable company, had suddenly achieved a cultural reach beyond what the likes of Robert Evans could ever have imagined. “Whoa—the minnow swallows the whale,” the former Discovery executive recalled thinking.

Under Zaslav, W.B.D. adopted a new slogan, “the stuff that dreams are made of”—an evocation of Hollywood glory borrowed from “The Maltese Falcon,” a hit for Warner Bros. in 1941. But Zaslav joined the movie business at a bracingly inglorious moment. The advent of streaming video has demolished old business models. The unions that represent the industry’s actors and writers are carrying out a bitter and prolonged strike. And the company that Zaslav has ended up leading is an ungainly entity, stuck with colossal debts.

Zaslav has said that he is focussed on the long term—a sensible position, since he’s made a pretty rough first impression. As soon as he took over W.B.D., he began slashing costs and laying off hundreds of workers. Last August, he scrapped a Scooby-Doo movie and a ninety-million-dollar Batgirl project, both nearly complete, and wrote them off for tax purposes. (W.B.D. justified the decision as “a strategic shift.”) On the picket line, actors and writers point not just at his compensation package—valued at two hundred and forty-six million dollars in 2021, the year he brokered the W.B.D. deal and extended his contract—but also at his seeming interest in playing mogul while the entertainment business implodes.

For many, Zaslav is something of an antihero, at the center of the town’s story for all the wrong reasons. Those in what one insider half-jokingly calls “the Hollywood deep state” seem unsure that he is up to the task of building a new entertainment-industry power under difficult circumstances. Even Zaslav’s supporters describe him as an outsider feeling his way along. “Notwithstanding David’s long and distinguished media career, he is a relative newcomer to the motion-picture environment,” said Alan Horn, a former president and C.O.O. of Warner Bros. and chairman of Walt Disney Studios, who has been hired as an adviser to Zaslav. “That generated a lot of scrutiny, and it can take a while to be accepted.”

The deal that created W.B.D. was, like many mergers, a marriage of convenience. A.T. & T. had bought Time Warner in 2018, as part of an attempt to expand into the entertainment industry. This was a radical departure from A.T. & T.’s traditional business, but the company was eager enough to open new markets that it was willing to pursue an eighty-five-billion-dollar acquisition and to fight off an antitrust suit from the Department of Justice. Three years later, it was equally eager to get out.

John Malone, Zaslav’s longtime patron, is widely considered a principal architect of the deal. A former cable magnate who was a powerful owner of Discovery, Malone is eighty-two years old, worth around nine billion dollars, and seen as one of the most formidable minds in business. The W.B.D. transaction, a Reverse Morris Trust, is a hallmark of his dealmaking: a complex maneuver in which a company spins off a subsidiary to its shareholders, then immediately sells it to another company, which forms a new entity in which the shareholders have majority control. A.T. & T. shareholders retained seventy-one per cent of the stock in W.B.D.; this exchange, executed by high-priced bankers and lawyers, prevented them from incurring capital-gains tax. Malone owns less than one per cent of the stock, but sits on the board and remains enormously influential. (Advance, the parent company of Condé Nast and The New Yorker, is one of the largest shareholders in W.B.D., with around eight per cent of the stock.)

Discovery didn’t really have the money to make the acquisition outright. A former media executive characterized it as a leveraged debt buyout, which is “unusual in the media business, because the media business is so volatile.” But the deal left the new company with substantial handicaps: Discovery, which was already carrying fifteen billion dollars of debt, went further in debt as it made a huge payment to A.T. & T. Thus, W.B.D. was born more than fifty-six billion dollars in the red. In order to keep his company intact, Zaslav would have to use its cash flow to pay down that debt. The former media executive told me, “The key is, in the next two to three years, can David pay off enough debt that he emerges with a viable business?”

The media industry is a seascape of big fish prowling for slightly smaller fish to eat. W.B.D.’s creation was Discovery’s bid to “scale up,” combining assets to compete with such streaming entities as Netflix and Amazon’s Prime Video, which have spent a decade enticing customers to cancel their cable subscriptions. The truism is that only the largest firms will survive in the post-cable world of streaming, which demands endless content. Traditional media companies have launched their own streaming services, but it’s been difficult for them to make scores of new movies and series while their once-reliable cash flows dwindle. Expensive cable subscriptions are quickly becoming obsolete. Advertising, too, has been lost to Big Tech, as Facebook and Google Ads have come to dominate the market.

Zaslav likes to tout W.B.D.’s vast library: “Harry Potter,” “The Lord of the Rings,” “Superman,” “Batman,” “Friends,” “Game of Thrones.” (He tends not to dwell on “Dr. Pimple Popper,” a reality series about a celebrity dermatologist.) His company, he boasts, is purely focussed on content, not distracted by selling phones or cloud storage or bulk toilet paper. But anyone who runs an enterprise like CNN or HBO knows that the days of easy money from cable fees have ended. CNN made a billion dollars in profit in 2016, and is expecting to make more than eight hundred million dollars this year—a good business, but a shrinking one. The future of entertainment might have been aptly described by Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, in 2016. “When we win a Golden Globe,” he said, “it helps us sell more shoes.”

Someone who has worked with Zaslav for years described his career as a series of cannily seized opportunities. Born in Brooklyn, he spent most of his childhood in suburban Rockland County, where his father was an attorney and his mother taught at a Jewish day school. Zaslav was a talented tennis player; Althea Gibson, the first Black athlete to win a Grand Slam, was his private coach. After graduating from Binghamton University and Boston University School of Law, he went to work for the New York firm of LeBoeuf, Lamb, Leiby & MacRae, where he endeared himself to partners by joining them for matches. “I wasn’t a good lawyer,” he later told Time. “But I was a good tennis player.” (Zaslav declined to speak on the record for this story.)

In 1986, the firm hired Richard Berman, a former general counsel of Warner Cable, who brought along MTV and Discovery as clients. Zaslav was quickly drawn to the work. “It wasn’t the law that I was passionate about,” he later said. “It was the cable business and the idea of building a business.” A few years later, Zaslav recalled in an interview in 2017, he happened upon a story in the trade publication Multichannel News, which said that Bob Wright, the C.E.O. of NBC, wanted to get into cable. Zaslav wrote Wright a letter saying that he wanted to be part of the project. Soon after, he was hired as a junior lawyer for what would become CNBC.

Zaslav has told the story of the letter many times, though recently it got a bit of a punch-up. In the version he delivered in a speech this spring, the article appeared not in Multichannel News but in the Hollywood Reporter, and the letter went not to Wright but to Jack Welch—the C.E.O. of NBC’s parent company and perhaps the greatest corporate celebrity of his time.

When Zaslav started at CNBC, “there were a few layers between him and Jack Welch,” a person who worked there at the time told me. The startup network operated out of Fort Lee, New Jersey, far from NBC’s Art Deco headquarters at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Eventually, Zaslav began overseeing the negotiations with regional cable companies over how much each would pay to carry CNBC. “David was a transactional guy,” the former NBC co-worker told me. “He went from deal to deal.” But Zaslav was ambitious. His deals often seemed timed to close on the night before a big meeting, and he would show up bedraggled but radiating victory.

[ad_2]

Source link