[ad_1]

It’s been a good few months for catching up on the work of the playwright John Patrick Shanley. Last fall, the Lucille Lortel Theatre put on a revival of Shanley’s seedy, stormy, aggressive love story, from 1983, “Danny and the Deep Blue Sea”—a production most notable, thinking back on it, for its announcement of a new level of ambition on the part of Aubrey Plaza, who starred as the tough, lost Roberta.

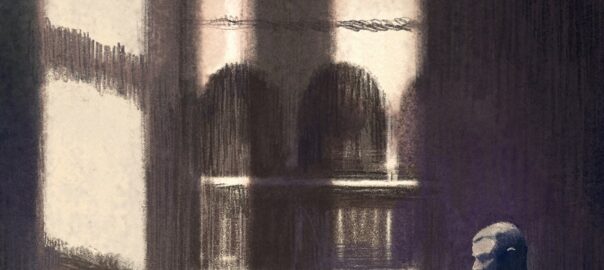

Now, this spring—the Lenten timing is appropriate, perhaps, for this God-haunted writer—there’s a Shanley double bill. “Doubt: A Parable,” his Pulitzer Prize-winning drama, from 2004, about a fraught episode at a Catholic school and parish, is in revival at the Todd Haimes Theatre, produced by the Roundabout and directed by Scott Ellis. “Brooklyn Laundry,” Shanley’s newest play, a tragicomic romance about the excruciating fickleness of fate, is at Manhattan Theatre Club’s New York City Center Stage I, under Shanley’s own direction.

Shanley’s plays are, in some ways, perfect examples of the form. He does the classic thing: gets people into a room and makes them talk in ways that spark unlikely action. He often writes for pairs, forgoing party scenes or crowded rooms full of overlapping speech; instead, Shanley frequently has one person meet up with another, one couple at a time, letting the conversation become dialectical, almost boxerly, coaxing new situations, social and personal, out of head-on verbal confrontation. If Shanley’s people occasionally say or do unlikely or unrealistic things, it’s only because of their preternatural willingness to roll up their sleeves and talk rather than fight. There’s a hint of violence in much of his work, just as the possibility of bloodshed hangs over so much political rhetoric. The subtext in both cases: all this yapping is what we do to stave off war.

“Doubt” is set in motion with a kind of philosophical discourse between two nuns. Sister Aloysius (Amy Ryan), the principal of a Catholic school in the Bronx, is an emissary of the past. She thinks that discipline is the true path to godliness and a proper education, and that a pedagogue shouldn’t insinuate herself into friendships with students. She’s scolding a new teacher, Sister James (Zoe Kazan), an obviously friendly, sweet presence. Sister Aloysius charges that the young woman is far too invested—to the point of a subtle narcissism—in how much her students like her.

Lines like these are good for a laugh, but their deepest implications get quite dark quite quickly. Sister James has noticed that one of her students, Donald Muller—the boy never appears in the play, but he is the locus of its most harrowing conversations—has become an object of special attention for the parish priest, Father Flynn (Liev Schreiber), whose poetic, intellectually pert sermon on the topic of doubt is the first thing we hear in the play. The priest and the child have spent time alone together, and after one meeting Donald returned to Sister James’s class acting strange, his breath redolent of sacramental wine.

Sister James is hesitant to assume the worst of Father Flynn: he seems like a nice guy, open and warm, and willing to consider secular songs such as “Frosty the Snowman” for the school’s Christmas pageant. Sister Aloysius hates that idea: “ ‘Frosty the Snowman’ espouses a pagan belief in magic,” she says. “The snowman comes to life when an enchanted hat is put on his head. If the music were more somber, people would realize the images are disturbing and the song heretical. . . . It should be banned from the airwaves.”

Father Flynn finds this attitude intolerant, and he invokes Vatican II—the ecumenical council whose purpose was to “open” the Roman Catholic Church to the modern world—as a prompt to lower the walls of formality among priests and nuns and the people they serve. But open doors and lower walls can create space for devils to stroll in unimpeded, and Shanley suggests how abusers might twist the logic of Vatican II to their own nefarious ends.

At its best, “Doubt” is about formality. Sister Aloysius anxiously adheres to the rules forbidding one-on-one meetings between priests and nuns. The only three-person scene comes when the nuns draw Father Flynn into Sister Aloysius’s office to ambush him on the topic of Donald. She wants to forestall the kind of tête-à-tête that makes up the texture of Shanley’s dramaturgy. When, at Flynn’s insistence, a one-on-one finally does occur, something like the truth starts to emerge just as the dance of formality fades.

Donald’s mother, Mrs. Muller (an affecting Quincy Tyler Bernstine), is summoned to Sister Aloysius’s office, where she’s alarmed by the formal setting; like anyone who has, at one time or another, been schooled, she knows that the principal’s office means trouble. She’d rather avoid that static. Donald is the only Black student in the school, and he’d transferred from a public school where “they were gonna kill him,” his mother says. Horribly, Mrs. Muller would prefer to have Donald, an eighth grader, stay “just till June”—no matter the nature of the relationship between him and Father Flynn—so that he can make it into a good high school and, later, into college. “Maybe some of them boys want to get caught,” she reasons. “What you don’t know maybe is my son is . . . that way.” Bernstine plays the role with touching pathos and monstrous control, the sort you only develop under the crushing weight of that worst American formality—the color line.

Just like “Doubt,” Shanley’s new play, “Brooklyn Laundry,” employs a series of deeply meaningful duets. Fran (a moving Cecily Strong) and Owen (David Zayas) encounter each other at a laundromat that Owen owns. Early in their first discussion, Owen breezily mentions God, and that sets Fran off. “Do you believe in God?” she asks, in irritated disbelief. “Yeah, why not?” Owen says. He “hit the jackpot” by winning two settlements and is now his own boss. Case closed. This question—although it never comes up again, at least not explicitly—is drastically important to the rest of the action. Fran is a bit like Biblical Job: she’s got a dying sister with two children, and before the play’s end more awful and unbelievable contingencies come flying into her life like a plague of locusts. She never stages a confrontation with God, or with fate, the way Job does, but the play keeps asking, as if stunned, why things happen as they do, and whether a budding love can survive the slings and arrows of a seemingly unguided existence.

As Fran talks and talks—not only with Owen but also with her sick sister, Trish (Florencia Lozano), and their other, more uptight sister, Susie (Andrea Syglowski)—it’s hard not to think about how two of Shanley’s lasting interests, on display brilliantly in these plays, fit together. God and fate on the one hand, talk on the other. Eventually, Fran and Owen have dinner, both high on mushrooms. The lights glow, and slowly their fears subside, and they start to confide. “This is the best conversation I’ve ever had!” Fran says. The unending volley of speech in Shanley’s plays, one utterance after another, is its own homegrown theology. Life makes better sense when you stop and talk it out. ♦

[ad_2]

Source link