[ad_1]

Yuskavage’s work has ranged widely, from small watercolor still-lifes of flowers, fruit, and nipples to huge, eerie landscapes, which feel like a dream where you’re not sure if you want to stay forever in the land of erotically tinged weirdness or wake up before something unspeakable happens. What has remained constant in her career is an extraordinary way with color, a penchant for scenarios that defy interpretation, and a fascination with rendering a particular kind of naked lady. “Why?” the curator Helen Molesworth asked Yuskavage in a recent interview. “Why have you made this outrageous, hypersexualized . . . white nude female figure the sort of centerpiece of your visual language?”

“Because,” Yuskavage shot back, “that’s the history of art.”

One summer afternoon in Paris, Yuskavage and Levenstein stood before Manet’s “Blonde with Bare Breasts,” at the Musée d’Orsay. “They’re so . . . presentational,” Yuskavage said, moving close enough to see the brushstrokes. “Kind of the greatest breasts in Western art, in terms of naturalness.” Asked why artists are so captivated by breasts, Yuskavage replied, “Everyone is obsessed with them. Go ask a baby.” For artists, she said, the challenge is finding a way to paint everything besides breasts with as much passion. “Because the tit comes with—”

“—inbuilt interest,” Levenstein finished for her. Levenstein, Yuskavage’s husband of thirty-one years, met her in art school at Yale. He had recently emigrated from the Soviet Union with his mother, a classical pianist, and his father, an engineer who had survived the Gulag: “I was wandering the hallways, totally lost, and she came out of a classroom to wash her brushes.” Yuskavage, who’d just gained the freshman fifteen, asked him, “Did you know Yale makes your breasts grow?” Levenstein gave her a bewildered look: “I said, ‘No.’ But I was willing to consider the possibility.”

Yuskavage likes painting roundness and volume in general. Many of her works are ornamented with brightly colored balls and beads—it’s as if they roll around her studio from one canvas to the next. They are a reference to one of Yuskavage’s favorite paintings, Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights,” which is dotted with mysterious berries being variously consumed, inhabited, and excreted. They are also a rebellion against the dictum that serious artists should never indulge in the decorative. “We went to art school at the tail end of modernism, and modernism is all about flatness,” Yuskavage said. “People didn’t render objects and, like, put highlights on them. You’d be considered a reactionary fool. So I always liked the idea of the wrongness of rendering. And then add to that you’re rendering a tit—that’s like double wrong.”

They moved on to look at “Olympia,” Manet’s portrait of a nude reclining in bed, staring directly at the viewer, as a servant presents her with flowers from an admirer. “She was a known prostitute,” Yuskavage said, “and it was considered very salacious to put her as the Venus. Manet is basically saying, ‘One of you sent her these flowers. This is not any old Venus: this is your Venus.’ ”

Giving the culture the nude that reflects its preoccupations—the Venus that it deserves—has been central to Yuskavage’s project. “I’m not capable of overlooking reality,” she told me. Her first show of work that felt true to her vision featured the “Bad Babies”: four young female figures looking angry, awkward, and uncomfortable, exposed from the waist down, suspended in Yuskavage’s luscious sfumato. “That feeling of the figure being caught in the paint was really interesting,” the artist Sarah Sze, a friend of Yuskavage’s, told me. “There was a kind of empathy you had for it.” To be young and female is to be looked at—to be trapped in being looked at—and Yuskavage made the looking as confounding for the viewer as it seemed to be for the subject. The celebrated figurative painter Kerry James Marshall said, “Lisa’s paintings call out in a fairly irresistible way, which is maybe one of the reasons that people have so much trouble with some of them. I mean, you’ve kind of got to say, ‘Is there something wrong with me? Or is there something wrong with that picture?’ ”

Unlike John Currin, who has also become famous for applying Old Master techniques to the vulgarity of the present, Yuskavage has never had a major museum retrospective. (“I was using soft-core porn first—just look at the dates,” Yuskavage said. “But it’s a bad idea, so, like, let’s not brag.”) Yuskavage was galvanized by a Willem de Kooning retrospective, held at MOMA in 2011. “Each room showed a very distinct body of work, and I was, like, ‘I could do that—I’m going to do that,’ ” she said. “And people are going to be, like, ‘I didn’t know she was that fucking good at it for so many years!’ ” She laughed. “I’m Little Miss Underestimated. They think I just do the tits.”

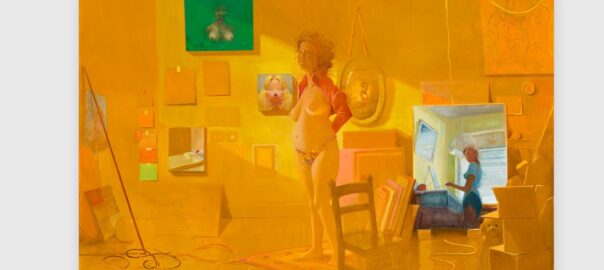

Most recently, Yuskavage has been painting surreal images of spaces where art is made. In “Golden Studio”—a massive work in the glowing colors of marigolds and honey—a woman with a rounded belly stands in peaceful contemplation, surrounded by empty boxes, extension cords, and, on the walls, what Yuskavage calls her “ground-zero paintings”—previous works that marked a leap forward in her evolution. The studio paintings feature prominently in her new show at the David Zwirner gallery in Paris, her first solo exhibition in France.

Yuskavage likes to invent rules to push against in her work, and for the new paintings she decided that she had to appear in each one in a cryptic form—as herself from behind, as her previous work, or as some kind of avatar. Self-portraiture has historically been considered a lower subject, which is to say a female painter’s subject; for much of the nineteenth century, women artists in the West generally weren’t permitted to work from nude models, so they turned to the mirror. But an artist who represents herself by painting her previous work in a fantasy studio is painting what she does, not how she looks.

When Helen Molesworth visited Yuskavage’s studio recently, she was impressed by the moxie of the new paintings. “I was, like, ‘Oh, snap! You’re really going to take this on,’ ” Molesworth said. Yuskavage was choosing a subject associated with Velázquez, Matisse, Vermeer, Braque, and van Gogh. “It’s the A-team all-stars all the way,” Molesworth continued. “If you were going to make a list of the great paintings, a lot of them would be studio paintings. And the reality is there are not a lot of pictures like that by women.” She added, “In my opinion, the scale and the ambition of that work exceeds something like having a show at a gallery in Paris: the ambition of that work is aimed squarely at The Museum—capital ‘T,’ capital ‘M’—as an institution.”

At the Musée d’Orsay, Levenstein and Yuskavage went downstairs to visit Courbet’s “The Artist’s Studio,” perhaps the most famous example of the genre. “He’s painting a landscape, with a nude model watching him—it’s so dreamlike,” Yuskavage said. “It’s got all the figures from his previous paintings. Time is folding in and out.” She had decided to call her own show “Rendez-vous,” because her paintings were a place to meet up—with the dead, with the techniques and tropes of other artists, with past selves. Yuskavage moved toward the center of the canvas, where Courbet had painted himself at an easel. “People are coming and going, it’s like a party, and he’s just working on this landscape dutifully,” she said. “Doing his thing and not noticing that anything else is going on.”

At the turn of the millennium, the Whitney Biennial featured three Yuskavage paintings: two luminous, lascivious nudes and a portrait of a woman who looks intelligent but uneasy, “her eyes rolled heavenward in the buggy, exaggerated style of an El Greco saint,” as the Times put it. The picture, “True Blonde IV (At Home),” appeared in ads on the sides of New York City buses. The subject was Yuskavage’s oldest friend, Kathy, with whom she has been close since their girlhood in Juniata Park, a gritty section of North Philadelphia. Kathy was the model for many of her early paintings—her first Olympia.

A few weeks before her show in France, Yuskavage was walking down Claridge Street, on the block where she grew up, and called Kathy to say she was in town.

“Oh, you’re slumming it!” Kathy, who still lives in the area, said.

“Kathy was always the pretty one, and I was the dork,” Yuskavage explained.

“You weren’t a dork,” Kathy told her. “You were smart.”

“You were smart, too, but you had your good looks to rely upon.”

“Yeah, they really did me right.” Kathy, who works as a train operator, gave a little snort. “I did so wonderful.”

When they were teen-agers, Yuskavage used Kathy as “bait” when she wanted to meet guys. Together with their friends, they made the “Tit Papers”: drawings and musings about their burgeoning bosoms. “We were always very sexual, even when we were little,” Kathy told me. “Not experimenting or anything, but talking about it and reading about it. Her parents had ‘The Joy of Sex.’ ” Yuskavage later made a series of paintings of images from Penthouse which she had examined with other kids in the neighborhood. She’d found them both arousing and confusing. “If this is a girl,” she remembers thinking, “then what am I?”

[ad_2]

Source link