[ad_1]

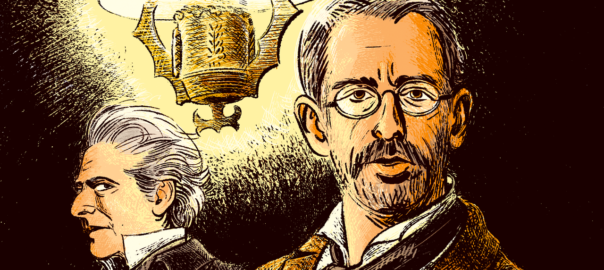

I don’t know if I’ll ever forgive myself for missing the Thursday, March 14th, preview performance of Henrik Ibsen’s “An Enemy of the People,” published in 1882 and revived at Circle in the Square, in a new version by Amy Herzog, under Sam Gold’s deceptively simple direction. At the climax of the play, there’s a town meeting in a raucous bar, the whole place fit to explode with civic tension and proto-Fascist violence. The theatre lights are up, as if to indicate that the audience is also attending the meeting, and Jeremy Strong, playing Dr. Thomas Stockmann, a scientist armed with the truth but lonely in its defense, is standing atop the bar, trying to get his point across.

At that moment of high drama, one environmental protester in the audience after another got to their feet and began to fulminate about the climate. “I am very, very sorry to interrupt your night and this amazing performance!” one shouted. “The oceans are acidifying! The oceans are rising and will swallow this city and this entire theatre whole!” The protest action, with its references to science and to government inertia, and with its tightrope walking along the boundaries of free speech, perfectly matched the tone and the content of the play. Many people in attendance thought (wrongly) that it was a contemporizing gag—a possibly corny play at relevance—planned by Gold. The truth can be an off-putting distraction. It changes trajectories; slows down the blithe, fleet motion of progress; makes your big night out at the theatre a weird and confusing ordeal.

Thomas Stockmann is a proud, sad, bombastic, socially clumsy, utterly sincere doctor working as the medical director of the baths in a cloistered Norwegian town in the late nineteenth century. He’s a widower who has become passionate about doing what’s right. His brother Peter (Michael Imperioli) is the mayor—and therefore, quite awkwardly, his domineering boss. Thomas likes to host young people at his house, though he has his daughter, Petra (Victoria Pedretti), do the real work of hosting: she serves food, pours drinks, entertains the retinue of journalists, seafarers, and political wannabes who are constantly stopping by. Thomas sits off to the side and admires their energy and righteous countercultural beliefs. He’s excited for the future, when they’ll take over.

The recently opened baths, Thomas’s remit, promise to be an important source of revenue for the town. Sick people from all over will come to convalesce and rest up. It’s inconvenient, then, perhaps catastrophically so, when Thomas reveals a finding that he’s been working toward in secret: the baths use water that has been contaminated by the local tanneries. It’s full of bacteria. (His father-in-law, first funny then menacing, calls the bacteria “invisible animals.”) After Thomas offers his report to Peter and makes a series of suggestions to right this potentially fatal wrong, a veil lifts, and Peter’s identity as, above all, a political operator, becomes evident:

This bit of climactic dialogue, hammered into plain yet insinuating and increasingly dangerous English by Herzog, is emblematic of this new production. Ibsen is a locus of particular interest for Herzog: her transfiguration of “A Doll’s House” last year, starring Jessica Chastain, took a similar tack. She finds the word-by-word humor in Ibsen and throws it like a huge, falsely comforting blanket over the social trouble that the plays describe. In her argot, Ibsen’s characters sound like slow-talking, fast-thinking products of migration across the U.S.—people with country manners and city coolness lurking within. Listening to her translations is like riding in a placid yacht over shark-infested waters.

Herzog’s take on Ibsen reminds me of Tomas Tranströmer’s gently troubling poems, as translated, from the Swedish, by Patty Crane. From “After Someone’s Death”:

In “Enemy,” a slow dread, first muffled but gradually made all too clear, is prompted by the organism of the town as a whole, fickle public, whose whims reveal another kind of invisible animal—discernible only by the steady changing of the collective mood. Peter is opposed to Thomas’s proposals from the start, but at the outset Thomas is supported by Hovstad, the dynamic publisher of a liberal paper (played in sharp, ironic, and deadly accurate style by Caleb Eberhardt). Hovstad, one of the young people who often gather at the Stockmanns’ house, has published several of Thomas’s ardent articles and seems to respect the older man. The paper’s printer, Aslaksen (the always excellent and here magnificently funny Thomas Jay Ryan), is a cautious moderate who promises to corral the working class and bring them over to Thomas’s side. But in the course of the play, for reasons both deeply personal and politically expedient, each man becomes an impediment to justice.

It was a masterstroke to cast Jeremy Strong in the role of Thomas Stockmann. He’s a patient, nuanced performer with an instinct for the rhythms of everyday talk. He and Herzog both find conversational menace like certain musicians sniff out a perfect pitch. He speaks at a measured pace but with constant urgency, almost a strain, even when Thomas is at his happiest, giving toasts and mingling with the people he thinks are his friends. His tenor has currents of impatient energy running under it. His declarative sentences turn upward at the end, like a series of unanswerable questions.

Strong’s public persona—as a dead-serious, process-obsessed actor (as portrayed in a Profile in this magazine), never hesitant to be an inconvenience if true art hangs in the balance—is at work here, too. Not unlike the sad clown Kendall Roy, from “Succession,” the character with whom Strong is most likely to be forever identified, Thomas makes grand attempts at rhetoric that don’t quite succeed, perhaps, paradoxically, because they are so earnest and deeply felt.

At the big moment when—stymied by the multiheaded hydra of the government and the press—Thomas tries to read his findings aloud, he does so in an increasingly tragicomic mode. Defending his own expertise, he makes a bizarre dog analogy: “There’s a difference between a stray and a poodle, isn’t there? There’s a fundamental difference. I’m not saying those mutts wouldn’t be capable of learning good behavior if they’d had the right opportunities, but I wouldn’t want one living in my house. . . . But somehow when it comes to humans—when I say I have studied biology, I know things you do not know, you should listen to me, that—that you can’t abide.”

It’s a perfect echo of the righteous but—let’s face it—heretofore largely ineffective pleas of climate scientists, whose cries from the heart have become the droning background to our march toward disaster. I sat in the theatre, the day after the protest, hoping that the activists would strike again, make one more nice, big mess.

When the protesters had marched toward the stage, causing barely comprehended chaos, both Imperioli and Ryan had initially stayed in character as they attempted to fend them off. Strong, though, authentic impulses all the way down, reacted as Thomas, on the protesters’ side. “Let him speak!” he implored. I’m certain he meant it. Thomas surely would have. ♦

[ad_2]

Source link