[ad_1]

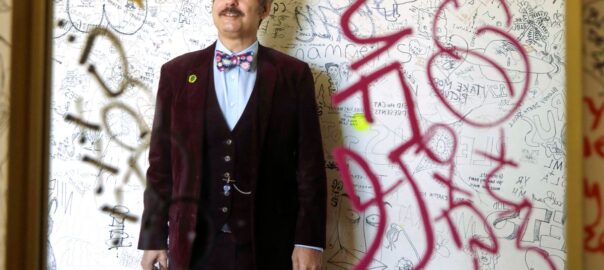

Photo: Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times via Contour RA/Contour RA by Getty Images

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It is a transitory life being a comedian. It is challenging professionally, as has been underlined recently by striking actors and writers sharing their stories of professional ups and downs. It’s also challenging creatively, where once you think you figure out what your thing is, the muses lead you to some new idea, medium, or technique. To look back at Paul F. Tompkins’s nearly 40 years in comedy — starting as a teen in the Philadelphia comedy clubs during the boom to working at Mr. Show and becoming a fixture of the L.A. alternative-comedy scene to his last 14 years as a comedy-podcast guest standard bearer — is to see a comedian adapting to a series of breakthroughs and setbacks. It has taken work, but Tompkins has exhibited resilience and a drive to always be as true to himself as a comedian as possible.

Over the last few years, Tompkins has slowly returned to stand-up after years away focusing on improv and podcasting. Instead of comedy clubs or alternative shows, he’s been performing stand-up as part of his Varietopia shows in L.A. and around the country. At every show, he’ll go up with 20-plus minutes of completely new material — mostly stories with silly digressions — that is as compelling and laugh-dense as most comedians’ finished products. He continues to perform improv around town and remains the guest all comedy podcasters aspire to land. Earlier this year, a week before the WGA strike began, Tompkins had a candid conversation about the how and the why, the good and the bad of how his comedy has changed over the last 20 years.

Were you always silly?

Oh, always. I was a real class clown, and I liked making people laugh. It was very validating to me in the most traditional, classic sense of, I want you to like me. It really meant a lot to me because it was not something that I was able to get at home. It was a huge thing to make my mother laugh, and we were a family that joked around a lot. There was a lot of roasting and stuff like that. But to get my mom to laugh rather than respond with something that completely deflated the humor of what I was trying to say or explaining to me, “Actually, this is why that is” … I know that’s why that is! I’m being silly! So when I could make my friends laugh or make a teacher laugh, that was huge. Making an adult laugh was a huge deal.

I can imagine your comedy is popular with kids.

Yeah, especially my early stuff because I’m just a silly, yelly man.

Putting aside Driven to Drink, your HBO one-person show, through the early 2000s your act was largely you as a silly, yelly stand-up. I think of jokes like “Peanut Brittle.” But over the last 20 or so years, it is clear your comedy and your relationship to stand-up have evolved significantly. I’d like to discuss how and why that happened. The first thing that seemed to directly impact your evolution was in 2003 you went to therapy for the first time. You’ve talked about the benefits for you personally. You also have, I think, one of the best jokes ever written about therapy, which is, “It’s not all just talking about your parents, but there’s enough of it …”

Not all about blaming your parents.

“… but enough that you feel like you get your money’s worth.”

Which I stand by. It is like that!

But it really seemed to impact how you approached stand-up. Can you talk about the influence?

I think, like a lot of people in comedy, I thought my fear was, If I become happier, I’m not gonna be funny anymore, but really, I was just afraid of therapy. I was afraid of, What if I found out terrible things about myself? What if I find out I’m a monster? What if I have a recovered memory? It’s really just the fear of the unknown. It’s the fear of finding out stuff about yourself that is not pleasant or is sad. It’s not like, Oh my God, I’m gonna be Hannibal Lecter. It’s somehow knowing in the back of your mind, I’m going to have to talk about stuff that I don’t want to talk about. That’s going to be uncomfortable.

What you don’t realize until you start doing it is it’s such a release to get these things out of your brain that you’re carrying around in your heart and soul for so long. Then to be talking to someone who can help you make sense of this stuff, it was just … What a tremendous thing that was for me. It was such a relief, it was such a help, it was such an aide, it was such a tool to have. And then finding out that it has no bearing on whether I’m funny or not. I’m still gonna have pain, I’m still gonna have sadness, I’m still gonna have frustration. I’m not gonna be healed, I’m not gonna be all fixed. It’s like a regular joke that my wife and I would have after therapy: It’s so funny to ask someone after a therapy session, “How’d it go?” So a joke that we have is, “All done! I’m fixed! Yeah, it worked!”

You figured it out! You have the answers!

Finally cracked it! I’m all done! I went to talk therapy for ten years straight, and then at some point towards the end there I got on antidepressants, which is another thing that was very scary to me.

Now I’m at a point where I could probably stand to go back to talk therapy again. The medication really helps, but it is good to have somebody whose job it is to understand these things, to understand feelings and everything. The only reason I stopped was I felt like I kind of hit a wall. I was talking about the same things over and over again, and I wasn’t able to move forward. Now I’m at a different point in my life, and I feel like I would like to go back and talk about stuff from where I am now.

So was the process of talking openly in therapy directly connected to doing so onstage?

I think it gave me the courage to try it, and once people responded to it, I realized I could do it because I really enjoyed that. I realized I could tell a story from my own life and tap into the emotional aspects of it, which was the way in for the audience. They didn’t necessarily have to have the exact same experience as I did. Laboring Under Delusions is the example of that for me, where I’m telling some very unrelatable stories, but the emotion of it is something — everyone’s been embarrassed, everyone’s been scared, everyone’s been whatever — and then I could talk about whatever I wanted, and the audience would not feel shut out.

The next breakthrough was podcasting. You’ve talked about in interviews and on podcasts about how, growing up, what you wanted to be was a guest on a talk show. You said, “I don’t want to be on SNL, I want to be the host of SNL.” And you sort of have done that. It’s like Steve Martin or Martin Short: You’ve set the standard for what a podcast guest can be.

It’s very flattering that you’d compliment me on that, and it does mean a lot to me. It means a lot to me that a lot of people ask me to be their first guest on their podcast. I guess it means a lot to me because I try to be a good guest.

What does that mean to you?

I think it means you’re not above whatever show you’re doing. You engage with the premise of it in good faith and with enthusiasm — otherwise, don’t say yes. The only time I regretted doing that was The Adam Carolla Show because I was not a listener to that show.

It was the early days.

I was there to promote something, and I didn’t realize that the show was Adam just goes and goes and you are there to support him. Like, he’ll take care of the comedy, and you chime in occasionally, but the spotlight is never going to be shone on you, really. It’s one of those things that I went on because I was told, “Look, this guy’s got a huge audience, so this appearance can mean a lot!” In retrospect, yeah, I’m sure that’s true, but I don’t enjoy doing things that way. It was not fun, you know? It was not fun to sit there and be part of the Wack Pack for an evening.

I don’t know, I’m not good at having a career, I guess … [Laughs.] Because there’s a lot of things like that that you should do because if you’re a good sport about that, and if you can do it over and over and over again, you can cross over into different audiences and do whatever. But it wasn’t fun.

I was listening back to those first few appearances you had on Comedy Death-Ray and Comedy Bang! Bang! And it was the first time you did Andrew Lloyd Webber, and at one moment, out of nowhere, you call Scott “Scottrick,” and it truly felt like a breakthrough.

100 percent.

Listening back, you can tell when you said that on that episode, something lit up in his brain and in you. Did it feel that way to you? Did you have a moment where you were like, There’s something to this?

Things like that are absolutely where you find the character, where it’s like it informs everything then. It’s like, Oh, this guy considers himself too fancy to use nicknames, and if there’s any name that seems like it could be a nickname, he’s going to assume it’s elongated to whatever. Then sometimes the trick was figuring out how to make everything more formal than it is, so if it doesn’t have a nickname, he has to make a longer version of it so that everyone is calling that person the nickname, but he’s not. And I remember it’s based on the last letter, like, Okay, so if Pat is Patrick, Scott is Scottrick. I remember the one with Adam Scott, so it’s like, Well, Adam, I guess it would be Samuel? So he’s Adamuel. Sometimes it’s a real reach, but that’s what it is! That’s what the guy is.

You’ve done characters in stand-up forever, but you’ve now become a prolific character creator through podcasting. How do you create a character when you’re doing podcasts? You really have moved away from impressions.

I started doing Bang! Bang! in 2009, I think, and my first few appearances were over the phone when Scott was still doing it out of the radio station, and I was in New York. I did impressions that I knew I could do already that came out of doing Best Week Ever, and “impressions” is very loose because it was caricatures, essentially, of famous people. Then I started looking for more voices that I could do when I started my own podcast, and then probably like … I don’t know, 2015, 2013, something like that, I think the first one I did was maybe J.W. Stillwater.

The idea of, like, I’m tired of doing these people who are tied to the real world — that felt like a limited thing to me. If I make up a person out of whole cloth, then I’m not confined to that. There’s no anchor to the real world; it can just be whatever it wants. It was also my way of learning improv without going to take classes — knowing the basic tenets and then improvising with people who were great improvisers, who knew what they were doing, and just trying to absorb as much of that by osmosis as I could. And also knowing that I was going to fail.

Honestly, the biggest lesson for me was being okay with that failure because I’ve always had a perfectionist’s streak, a control problem, and it would bum me out when things that I wanted to do, things that I would put onstage in a show, didn’t work. When there are a lot of moving parts and if a thing did not get pulled off properly, it made me mad. It made me mad to have to rely on other people in that way. It made me mad that I wasn’t able to communicate the thing that I wanted to communicate adequately enough. It made me mad that I only had one shot at it, and I couldn’t do it again, and it didn’t work the way I wanted it to work. So doing characters and doing improv — that’s the whole thing that’s built into it: Sometimes it’s not going to work, and you have to be okay with it and move on to the next thing. Not only do you have to move on in the moment, but after it’s done, you have to shake it off and take what you can from it as a learning experience and apply it to the next time you do it.

That was how I learned improv, and it also had a profound impact on my life. It made me more okay with things not being the way that I wanted them to be. It made me more okay with trying something and not being good at it, trying something and failing, and saying, “Hey, I’m coming at this with the right intentions, and if it doesn’t work, it’s not because I’m a bad person. It’s not because I can’t have anything the way I wanted. It’s just that this is life.” Life is more about trying things and not succeeding than it is about succeeding, and I needed to be okay with that. Honestly, I think some of the bigger disappointments that I’ve had in my life since I started doing improv would have been more devastating to me had I not learned those lessons.

The third thing that seemed to really change things around this same time period where you were doing podcasts is your parents passed. Your mother died in 2007, and then a few years later your father died. What was their relationship to your comedy, and how did it impact you to have them pass away in that way?

When one parent dies, it changes the landscape of your universe utterly. I don’t want to get into the nuts and bolts of it with people a lot because it’s sort of like a spoiler alert, you know what I mean? Unless you have absolutely shitty parents, which a number of people do, it’s extremely scary to think about. My parents were always older, so it’s a thing that I thought about a lot, but thinking about it versus when it actually happens are two different things. Nothing can prepare you for it.

Another thing about your parents dying is that your relationship with them does not end. You turn things over in your mind, and you look at them with fresh eyes every few years. As you go through stages of life, you think about where they were, and as you are the recipient of the good things of the time in which you live, you realize that they did not have the opportunities that you do, you know? On any given day, I am very forgiving of them and very resentful of them, and that just goes on and on as I continue to age.

That is where my desire to become funny came from. Again, getting back to the idea of therapy and, Am I gonna be as funny if I’m therapized? Well yeah, I still am. But would I have gotten into comedy had my relationship with my parents been different? I don’t know. There’s some people who have great relationships with their parents, who are some of the funniest people I know — like, professionally funny …

Who still have a need to do comedy regardless of that.

Yeah. Who knows where it comes from? It’s too simple to say my desire to be approved of made me a comedian. That’s what it feels like, but maybe I would have done it anyway. Maybe if my parents had laughed at every single thing I said, I would have said, “Hey, I’m funny! I should do this!”

I love the approval!

Yeah, this is great! It’s fun! That’s the thing: For whatever reason you get into stand-up, whatever pain you feel may have driven you into it, once you get into it, it’s like, This is fun! It’s not a pain factory. It’s not about angst. It’s not about whatever your demons are. It’s like, This is a fun thing to do! You get up in front of an audience, you make people laugh, you have a shared experience! It’s a ball, you know?

Can you talk about how these breakthroughs changed your relationship to the audience?

The change was, I think, in the simplest terms, I will let you in if you will let me in. The shared experience, to me, was the high to chase because there’s nothing like it. There’s nothing like when you hear a laughter of recognition about a heavy thing. It is so cathartic.

When people would come up to me after a show, especially when I was doing material about my mother’s death, they would say, “Hey, my mother died recently, and that really helped me.” I’m not looking for that, but when it happens, it’s very humbling — which I didn’t understand when people would say things like that, and now I get it. For someone to say that to you is an extraordinary gift, and that’s not something that you take lightly. When somebody says, “A thing that you said helped me,” that’s huge because of course I’ve had that experience with other things, you know? That’s no small thing to me when somebody says that to me, and it is very humbling. All I can say is, “Thank you for telling me that, and I’m glad that I could, in any way, ease your grief or give you a tiny moment away from it. I am hugely grateful to have done that.”

You started doing comedy in the ’80s — a time when you win over an audience, then destroy them. Your relationship is transactional.

100 percent. That’s what it felt like at the time.

But around 2009, 2010, your stand-up started feeling really open. I remember seeing you then, when you would do a set of just riffing. The energy was very, I am starting with nothing, and together, we’re going to see what we can come up with. Anyone familiar with your stand-up knows what I’m talking about. It sounds and feels like prepared stand-up, but it is clearly generated on the spot. I was curious what that felt like in the moment.

There’s still an element of scariness to it. Sometimes I’m more prepared than others. Sometimes I have stuff on the page, sometimes I don’t, and sometimes it’s this time of the month when I do this show and I have to talk about something. Then I have to sit and think, What has been sticking in my mind? What is a thing that has happened? What is a thing that I’ve observed? I have to let myself be open to it not being a perfect comedy idea. I’m still learning.

I had lunch last year with a friend of mine, Joe Randazzo, and I was kind of frustrated. I didn’t know what I wanted my stand-up to be, I didn’t know what I wanted to talk about, and he sort of let me off the hook. He said, “You can talk about whatever you want. Nobody’s going to fault you for it not being a heavy, deep topic.” And I was like, “Man, you’re absolutely right.”

There’s a thing that I call “the tyranny of the template,” which is when you think you’ve figured out, This is what I do, and it goes like this, and then you start trying to just refill that template over and over again, and you’re like, “I hate doing comedy!” I’m putting myself in a box, and that’s why I’m angry at it — but I’m in control of the box! I’m the one who’s building the box, and so it can be whatever I want it to be. But I have to remind myself of it because when you get into a groove with a template, you’re like, This is great! Then after a while, when you’ve kind of learned that thing, it becomes boring, and you don’t want to do it anymore. I have to be vigilant about that because I can talk myself into thinking, I don’t like doing this thing anymore — when in reality, I don’t like the way I’m doing it right now.

You were going through creative change while both the art form of comedy and the business of comedy were changing radically. Did it feel like that at the time?

Not really. I mean, my creativity was very much anchored in my sense of who I was as a person. Whether I’m talking about personal stuff or not, this is personal. This is me and my expression of art and humor. And much like in the way when show business can be tough, I would think, Man, I wish I could do absolutely anything else. I wish there was some other skill, some other thing I loved doing that’s easier than being in show business. I would think, I wish I could be a different comedian, a comedian that people wanted more. I could be more successful, but I can’t. This is just what I do.

I’m fortunate to have — and grateful to have — an audience of people who like what I do enough that I can sustain myself. You cannot ask for anything more than that. Anything else that happens is gravy. The fact that I can make a living, put a roof over my head, and keep it that way by just doing what I do — man, that’s not nothing, you know? Yeah, there’s always things that I would wish for more. Sometimes I wish that as much fun as it is to do a bunch of different things that make up my career, boy, wouldn’t it be nice to have one steady gig? I go to this place every day, I shoot this TV show, and then I can do all these other fun things without the scrambly aspect to it.

Maybe I’m wrong, but did you stop doing stand-up for a few years?

I did, yeah.

Was it a deliberate decision? It’s hard for stand-ups to be like, I’m going to stop doing stand-up.

Absolutely.

Walk me through that arc of deciding to do that.

Really it was a despair. My last special, which is called Crying and Driving, which I recorded in 2015 … The special that I had done before that, which is Laboring Under Delusions, was for Comedy Central, and I was really proud of and really enjoyed doing and was paid very well by Comedy Central just to perform the thing. When it came time to do my next hour, which was just three years later, I went to Comedy Central, and they offered me literally one-tenth of what I had made for the previous special. I remember talking to my agent and saying, “Man, this deal really sucks. I don’t know if I should take this.” I’m sure I probably used the word “insulting” or something. My agent said, “Well, on the other hand, they are the only ones that are making an offer,” and I could not disagree with the logic of that. So I swallowed my pride, and I put all the money into the special — I did not make anything from that special at the time — and I said, “I’m just going to make the best special that I can do,” and that was it.

Then it came and went. It aired on Comedy Central; I don’t know who watched it. I was told that for the last one I did, the numbers were pretty good. You know, one has this assumption in showbiz from what I’ve seen — I keep distancing myself from it, but because this is common to a lot of people I know — I would see other people and be like, The idea is you keep going up and up! So I had not only plateaued, but now I was going back down. There was a feeling of, Wow, people are just not interested.

In the intervening years, I had gone from wanting to be a guest on a talk show to wanting to host a talk show, and I wasn’t able to make that happen. I did a pilot for Comedy Central, and then after the pilot was told directly by the head of the network — this is before the official “no” came — but I was told, “Yeah, you come off kind of old-fashioned and stuffy, and that’s just not really what our audience wants. You made some casting decisions with the guests that I think hurt it.” And I was like, “Uh, you saw every step of this process! You’re not seeing this for the first time as the finished pilot. You know all the stuff that I did.” It felt really brutal to me. If you’re not going to pick it up, that’s fine, but this is literally a personal attack saying, “The audience doesn’t like you.” You can say, “It didn’t go well.” I can fill in the blanks myself.

But that was a real, real turning point to me. Then having that special happen a couple years after that and have nobody be interested in it, I thought, This is the one thing I always thought I had, which was stand-up. I was always successful, I had some stature in this world, and now I’m realizing I don’t have that stature anymore, and there’s not really a big market for the kind of thing that I do. So I was finding joy in doing improv and working with other people and learning this other sort of life thing, but I couldn’t go back to stand-up. It just hurt too much. It really hurt.

There was a period pre-pandemic where I tried to make myself go out and do sets, and I just wasn’t feeling it. It was just going through the motions of doing it, but I wasn’t connected with the material, I wasn’t connected to the audience, and it felt bad. It was really alarming, like, This isn’t how this feels! This is really weird! I don’t like this. So I just went where the joy was, and coincidentally, where the money was. I was getting good money for doing an improv podcast, so it’s still an ongoing process.

I don’t know if I’ll ever do a special again. I would like to, but knowing it will have to be self-funded is not my favorite thing in the world. Even though I’m grateful that this kind of world exists where I can go to Lodge Room or someplace and put on my own hour of stand-up, I still have the memory of doing Laboring Under Delusions at the Alex Theatre, which is this huge, beautiful theater, and knowing that the audience is a big audience of people that are there to see me, and having that feeling of like, It’s never gonna be like that again, you know?

But you feel that way?

I feel that way, and also, I’m older and I’m cagier, and it’s like, How much do I allow myself to believe in and get my heart broken again? How important is that to me? There’s certain jobs that seem to come up, and my wife is like, “You should tell your agent you’re interested in that!” And I’m like, “Man, I could be interested in that all day long, but that doesn’t mean people are interested in me doing it.” On the one hand, what more could you ask for than a partner that believes in you like this? I have to walk that line between, When am I being needlessly pessimistic, and when am I being realistic? It turns out it’s a finer line than I ever would have thought, and I don’t want to be pessimistic, but I also want to be realistic. I don’t want to waste my own time or anybody else’s time. But I don’t know. That shit is not up to me.

What’s it like when you do stand-up now?

I feel like it’s coming back to me, and the more I do it, the more comfortable it’s becoming. Right now, the feeling that’s coming back is the duck-below-the-surface-of-the-water kind of thing. I’m lucky that I’ve always been able to project a certain amount of confidence regardless of what’s happening internally, but I am getting back into — it is coming back — the enjoyment of doing it and the feeling of connection. Part of that is, honestly, getting used to a new space where I’m doing a show and feeling at home in that green room and stuff like that and feeling like this is my house. That kind of adds more than I would have suspected previously.

Watching recent Varietopias, the other thing I was so struck by was how much you love comedians and how much you love new comedians. Obviously, you’re figuring out a relationship to stand-up, but there’s not a bitterness that I think that can happen in showbiz.

I hope not. That’s a constant fight, and I think that for a lot of us in this business, jealousy comes with the territory. You have to keep your eyes on your own paper, and that is very hard to do.

The real thing you have to fight against, though, is bitterness because that’s the end. That’s the absolute end. It feels bad, it looks bad, it’s terrible. For me, I have to be really vigilant because I have friends that I can trust, and we can blow off steam, but I have to be very mindful of, like, Am I doing this too much? Am I taking too much delight in this person’s downfall? That’s not about any one person — like, if somebody didn’t get what they wanted, it’s like, Am I too happy about that? Or, Am I too much enjoying shit-talking behind somebody’s back because I’m jealous of what they have? If it used to be, That should be me, now it’s more like, Well, that was never gonna be me, so I might as well make fun of this person.

It shouldn’t be anybody.

[Laughs.] “It shouldn’t be that guy!”

Is there a certain amount of salvation in embracing the successes of new comedians?

Oh, for sure, yeah! I mean, it does help to keep me away from that bitterness. I remember Beth Stelling’s special Girl Daddy that came out — man, to watch somebody who has like … When you see the thing where they have come into their own, and they fucking got it, and it’s down, and it’s funny, and it’s deep, and it’s insightful, it’s entertaining, it’s everything — when you watch them become that, I get chills talking about it. I had to refrain from texting during the special. I was like, “Watch the whole thing!” And to say, “Beth, I love this special so much, congratulations.” I have to pull myself back from saying, “I’m proud of you,” because I don’t have any right to say that. I didn’t have any hand in her ascension!

“You did everything I told you about!”

But I felt that way, you know? I did feel that pride. To see somebody get to that point where it’s like, “You fucking did it! You’re so good! This is where you have cemented your status as one of the great comedians!” When somebody puts out one of those hours that’s unassailable, how can you not be excited by it?

Did you have a moment with your own stand-up for that?

Yeah, I think Laboring Under Delusions. You Should Have Told Me is the one where I talk about my mom dying, and that was very personal to me, and I felt like I had cracked something. I, unfortunately, ended up touring on that hour after I shot the special but before it came out, so it got better after. But Laboring Under Delusions, I worked so hard on that, and that was the special where I was like, This is me. This is who I am. This is the purest expression of me because it’s personal but it’s silly. I really, really worked hard on keeping it as tight and funny, and I wasn’t afraid to get into the emotions of some of the things, I wasn’t afraid to be vulnerable. It was, I think, the best night of my career, I think that’s safe to say.

How do you feel about your old, less personal material like “Peanut Brittle” now?

I mean, it really makes me laugh. I still think it’s really funny. I think I’ve done two encores in my life, which is a very strange thing in stand-up, and I don’t have anything prepared. It’s like, All the material I just did, that was it! I wasn’t saving anything! So that is the bit that I did both times, and it feels very strange because most of the crowd has already heard that bit, and it’s very weird to be setting it up like a new thought.

The conceit of stand-up — and everyone buys into it — is I’m saying this for the first time. Of course I’m not. Of course I’ve worked on it before and blah blah blah, and by the time you’re seeing it in this incarnation, I’ve done it a million times, so it feels very weird to break that conceit. But it’s still really very funny to me, and it’s really fun to perform. If I have to do a short set on something, like for a benefit or something like that, I’ll bring that back and do it.

Oh really?

Yeah, and it’s really fun! It’s really fun and silly, and I love performing it.

I ask because do you know the comedian Rose Matafeo?

Yeah. Rose is so funny. Her most recent special, Horndog, is so great. She also opened my eyes to things that could be done like incorporating video and stuff like that. I love that special so much. It was so good, and that was my first time seeing her do a long set. I adore Rose, and her sitcom, Starstruck, is great; she’s great on Taskmaster. I am a huge fan of Rose’s.

The Guardian asked comedians their favorite jokes, so she talked about “Peanut Brittle,” and she said, “I attribute most of my comedy and taste in style to this routine. I learned so much about rhythm from Tompkins. Great stand-up requires an equal balance of strong performance and strong writing. When you see the perfect alchemy of those, it feels like actual magic. I love Tompkins for all the reasons I love comedy: He makes the obscure or niche into something relatable with stupid voices, shouting, and celebration of shared human experience. That’s comedy, baby.”

That’s as wonderful an epitaph as you can ever ask for, you know? That is very meaningful to me.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

[ad_2]

Source link