[ad_1]

Kasper seems to have encountered Pound’s writings around 1950, when he was a student at Columbia. Martin gives the impression, as have others, that Kasper was a graduate of Columbia College. This is a little misleading; his degree came from Columbia’s School of General Studies, an adult-education program. At the time, Pound was in a mental hospital, St. Elizabeths, in Washington, D.C. He had been there since December, 1945, when he was declared unfit to stand trial for treason, a charge stemming from his broadcasts on Italian radio during the war. (He made hundreds of them, from 1941 until his arrest by American forces, in 1945.)

In fact, Pound was never medically diagnosed. It’s possible that the American government did not want to be in the position of executing a poet, and putting him in St. Elizabeths seemed the most convenient way to hold him accountable. Pound called it “the bughouse.” He would not be released until 1958, when he returned to Italy (something that the government should have arranged a lot sooner).

Pound was not crazy, nor was he repentant, and he received a steady stream of visitors to his hospital room. One was John Kasper, starting when he was twenty-one years old. Pound was always good to his disciples, and Kasper was more than a disciple. He was an acolyte, something that Pound, situated as he was, couldn’t resist.

Fighting desegregation was not high on Pound’s list of causes. The Jews were his lifelong obsession, and it was his antisemitism that first drew in Kasper. Pound was also a Jeffersonian, however. He hated the federal government—which was secretly run, of course, by Jews—so he could get behind the states’-rights argument against court-mandated desegregation.

Kasper had socialized with Black people at his bookstore (he opened one in New York City but relocated it to Washington, apparently to be closer to Pound), and he had even dated a Black woman. But he recognized that anti-integration agitation was not incompatible with the Poundian program, which included a horror of interbreeding. And both men agreed that the N.A.A.C.P. was a tool of Jews and Communists. Pound gave Kasper encouragement and free rein to wreak what havoc he could. As he put it in a letter to a friend, Kasper “at least got a little publicity for the NAACP being run by kikes not by coons.”

Kasper and Pound were in touch continually, to the point that their public association delayed Pound’s release from St. Elizabeths. The Justice Department needed Kasper to go away before they were willing to set Pound free. After Pound got to Italy, Kasper tried to reach him, but Pound avoided him. They never met again. But during the period of Kasper’s anti-integration activism Ezra Pound was in the mix.

Another odd wrinkle in the Clinton story has to do with the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government, the group that supplied the list of people Kasper called in Clinton. Martin mentions this group in passing. She doesn’t tell us that the federation was founded in 1955 by a man named Donald Davidson, who served as its chairman. (His vice-chair was a sculptor, Jack Kershaw, who once defended his statue of the Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest by insisting that “somebody needs to say a good word for slavery.”) Davidson, a poet, essayist, and journal editor, played a role in the founding of a method of literary interpretation called the New Criticism.

The New Criticism arose at Vanderbilt, in Nashville, where Davidson taught, and nearly all the first generation of New Critics were Southern partisans and Yankee-haters, opponents of secularism, liberalism, and modernity. Davidson was among the men behind “I’ll Take My Stand,” a now notorious anthology of pro-Dixie, anti-Northern ideology by Southern writers and professors.

The New Critics addressed the South’s race problem mainly by avoiding the subject. They were formalists. Politics wasn’t meant to play any part in their criticism. Davidson was the exception. In 1948, when the Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond, of South Carolina, ran for President on a segregationist platform, Davidson was an enthusiastic supporter, and helped get him on the ballot. (Thurmond carried four states.) By the time of Brown, Davidson’s overt racism had alienated most of his former Vanderbilt colleagues.

Davidson was not a bomb-thrower like Kasper. He was what Martin (who doesn’t mention him) would designate a “law-and-order segregationist.” He campaigned for a legal reversal of Brown, though it was not clear what body, apart from the Supreme Court, was in a position to do such a thing. When classes started in Clinton, the federation organized a rally. (Davidson was in Vermont, teaching at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference.) And it petitioned an Anderson County court to enjoin the high school from admitting Black students, on the ground that a Tennessee law prohibited integrated schools from receiving state money. The suit backfired when Davidson appealed and the Tennessee Supreme Court seized the occasion to declare the state’s school-segregation laws to be unconstitutional.

All the original New Critics except Davidson had moved North by 1956, and the New Criticism had become the dominant mode of literary pedagogy and interpretation in the academy. As for Pound, he was not cancelled; his literary reputation hardly suffered. His publisher, New Directions, kept issuing collections of his writings. Among Pound’s visitors at St. Elizabeths was virtually every important American poet, who would listen to him while he explained how things were and how things ought to be. These people all knew what Pound’s politics were, including the antisemitism. They just put it aside as a regrettable eccentricity.

In 1957, Kasper and a dozen other activists were put on trial for defying an injunction against interfering with the desegregation of Clinton High. Davidson’s federation supported many of the defendants financially, and when seven of them (including Kasper) were convicted Davidson issued a statement. “The jury stand sat a bulwark between potential judicial tyranny and the people,” he said. “The jury sitting in judgment . . . will go down in history as a tragic failure.” Which sounds like an argument for jury nullification.

It was just over a year after the desegregation of Clinton High that Eisenhower finally unsheathed the sword. When the governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, called on the state’s National Guard to prevent nine Black students from entering Central High School, in Little Rock, Eisenhower, after agonizing privately, federalized the Guard and sent in the 101st Airborne, to insure the students’ safety. The Black students were able to attend.

But the following fall the state legislature closed all public high schools in Little Rock for a year. Southern states had always threatened this as an option. In 1959, Prince Edward County, in Virginia, closed its public schools for five years. Speed was very deliberate across the South. By 1964, ten years after Brown, less than two per cent of Black students in the South attended school with whites.

What happened in Little Rock is better known than what happened in Clinton in part because Little Rock was the first time that the federal government sent troops to enforce a desegregation order (it would not be the last), and in part because the Arkansas government, unlike the Tennessee government, actively resisted court desegregation orders and barred Black students from entering a white school.

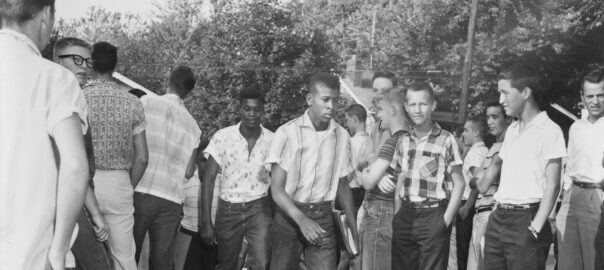

As familiar as the school-desegregation story is, a couple of things jump out in Martin’s telling. One is how profoundly divided the races were in the Jim Crow states. They had no conception of each other’s “lived experience,” as we would call it today. The white people in Clinton knew nothing about the Black people. Because segregation seemed to work so well, whites appear to have assumed that Black life was separate but similar.

In the Murrow documentary, David Brittain, the Clinton High School principal, was interviewed at length. The campaign of harassment against him had clearly worn him down, and he struggles to explain what it had been like. “It just presses you down every day, lower and lower,” he says. “And to me it is an amazing thing that an American citizen living in the United States has to be subjected to this while the lawless citizens, those who refuse to abide or accept the law, continue to run free.” Did it occur to him that he was only feeling something that every Black person in Tennessee felt every day?

The other striking thing in Martin’s account is that virtually every white person involved in the desegregation of Clinton High School was a segregationist. No one, except possibly some of the teachers, was actually in favor of integration. That included the principal, who did not permit the Black students to interact socially with the white students or to participate in extracurriculars. (The law said that they could get an education; that was it.) It included the governor, who, after sending in the National Guard, largely washed his hands of the mess. It even included the minister who was beaten.

[ad_2]

Source link